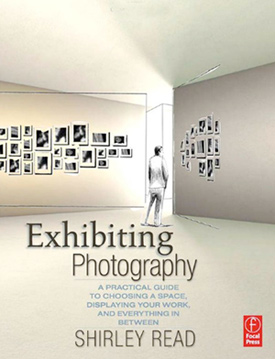

Shirley Read

Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-240-80939-7

257 pages, softback. £17.99

Exhibiting Photography comes at a time when there is a groundswell of college courses in photography, evidence of many regional support networks for the medium, a number of prizes and exhibition opportunities, several dedicated magazines, websites, galleries and projects that are all championing photographys status as a creative medium. Photography is, as Tom Normand proposes, the visual form of our age. In the books bibliography, Rhonda Wilsons publication Seeing the Light, A Photographers Guide to Enterprise is cited, a book which demonstrated (in 1993) that critical practice and career development are not mutually exclusive. Wilson is now the Director of Birmingham based Rhubarb Rhubarb, the annual international portfolio review event, an occasion which typifies the range and quality of photographic image-making today, whose participants, both reviewers and makers, should be alerted to this book.

Exhibiting Photography, however, is not initially an appealing book its cover is unattractive with a dull typeface and bland illustration (should have used a photograph) and is an immediate turnoff. Begin reading and you are faced with an explanation of the differences between the English and American uses of words related to exhibition practice (which suggests this has been written for a US market its publisher Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier, who publish scientific and academic books and journals). But this initially patronising and oversimplifying tone (derived from student workshops?) disappears after the preface and there is a lot more value in what is to follow.

The books mission is to improve the ability of image-makers to successfully negotiate the complexities of exhibition production in a step-by-step guide to the social, strategic and organizational skills that are expected in the public and commercial gallery sectors. Targeted mainly at the emerging photographer covering both amateur and professional its starting point is that moment when the image, in the eyes of its maker, is finished. From that point a number of practical, aesthetic and presentational choices present themselves. A photograph has to qualify as art. It does this through a process of negotiation involving a number of people whose job is to deliver it to an audience. These includes the framer, the curator, the gallery staff, the reviewer, the funder, the peer support group, as well as the public. Hopefully, in different ways, this book speaks to all of these, and is a timely reminder of the way those roles are interdependent.

The book is structured around 6 chapters, mainly giving practical advice, but punctuated with quotes from photographers and artists that open it out into a more general discussion. It also includes a number of useful Handouts (Sample CV; Model Release Form; Resources File; Toolkit checklist, The Budget; Press Release ) and several Case Studies, which lift it from its purely instructional base.

There is an empowering message in here that artists can do it for themselves by setting up their own structures and being in control of the discourse around their work. Photodebut, the second case study in the book, is a good example of a group project that promotes, supports and seeks to connect emerging photographers. Esther Teichmann recounts the initial collective as being self-propelling and exhilarating and remarks: Dialogue needs community and creativity thrives upon dialogue. This triangular relationship between creativity, dialogue and community, which is the foundation of all fine art education, often gets forgotten outside the framework of the academy . Following a different model TRACE is an artist-led curatorial and publishing project that aims to give artists the time and space to develop projects through exhibitions, editions, and publications. Photographer Sian Bonnell is upfront about whats on offer when artists exhibit in the TRACE space in Dorset, based in a domestic setting and in a former shop: a private view and talk (recorded on video), documentation of the show, a set of postcards and a fee. They also mentor photographers, review portfolios and offer guidance on editing, presentation, and new directions. The goal is for the photographers to take ownership of the networks for themselves, with TRACE acting as catalyst and the website a conduit.

Andrew Dewdney writes an overly long and optimistic piece on The Digital Gallery in the fourth case study, making interesting if contestable claims on the instability of a photographic oeuvre, A student could now undertake a very successful degree course in photography with no more than a mobile phone and an internet connection, because right now everything is about the circulation of the instant, real-time image the total ephemerality as well as the dissolution of the photographic image.

The superficiality of the art world and its dual sophistication are touched upon in Chapter 1, the richest of the six chapters: One of the ways the art world works is through a system of connecting institutions, organisations, and individuals. Many exhibition opportunities come about fairly informally by word of mouth and through conversation among curators or photographers. A subsequent section says that curators establish the meanings and status of contemporary art through its acquisition, exhibition, and interpretation. Here the author takes the opportunity to lambast the shallowness of contemporary curation while making the case for a blend of creative and admininstrative skills that a good curator would bring to the task of making work coherent: The curator is creating a conversation not just between artist and audience but among the artist, the audience, the space, the institution, the press, and the art world. And former Director of Brighton Photography Biennial, John Gill (whose quotes throughout the book seem disproportionate to the others selected for inclusion) remarks: 90% of the business of putting exhibitions together is in the organisation of it.

The final chapter, looking at hanging methods and pre-opening preparations becomes confused with a section on the Print Sales department of Photographers Gallery which suggests that this should have been signposted as a sixth case study in the book. The conclusion is surprisingly brief making the book seem unbalanced. A salient quote or challenge to the reader would have saved it from a rather deflated ending excepting of course, a useful glossary of terms. Lets hope the flaws in design and the numerous typos are addressed in the course of a second edition. In the meantime, theres enough essential stuff in here to help photographers, as well as college lecturers, curators, and facilitators in picking up the loose ends of current exhibition practice.

Malcolm Dickson

This review was published in Source magazine, issue 57, Winter 2009.