Stills Gallery, Edinburgh, 6th March 2009.

This event was advertised as a discussion that would explore the themes of photography and the city through distinct perspectives. Indeed, Alex Law, Duncan Forbes and Francis McKee approached the subject from three very different points of enquiry.

Alex Law began the discussion by offering us a look at 20th Century social theory through the work of Walter Benjamin, Henri Lefebvre and Georg Simmel. His paper was insightful, and surprisingly more relevant to photography than I had anticipated.

Law discussed Simmels The Metropolis and Mental Life (1903) and how the urban environment has transformed our personality over the years through the adjustments the city imposes on people. His talk covered broad themes, including the visual imagination of the city, the bombardment of our senses, the dialectic of the city, the domestication of the street and more generally, modernism and modernity.

Law outlined the inherent tensions between commodity production and peoples values and individuality. He touched upon Marx to illustrate that to make sense of history, we must leave the world of surface appearances and ideology and instead examine the material realities of labour and the dissemination and control of information if we are to obtain the truth. Importantly, Law discussed the idea that experience itself is becoming devalued, and that many thinkers (from Simmel to Adorno) believed that Art is the solution to the rescue humanity from experience.

Benjamin was one of these thinkers who saw art positively. For example Benjamin argued that with advances in technology such as photography, there is increased scope for human agency in the creation of art works. Yet in many ways this put him at odds with the pessimism of Adornos critique of the culture industry, and its standardisation of the production of art works.

Duncan Forbes went to offer us a reengagement with the history of photography. He focused on picturesque Edinburgh, the politics of the structural nostalgia and the romantic imagery this enforces. He outlined that in the 1820s there was an explosion of images of the city. Edinburgh was emerging as a spectacular city, and according to Forbes this spectacular had a dramatic effect on social relations.

Forbes described the arrival of the camera as a revolutionary instrument. Through an intriguing slideshow of photographic calotypes we were offered a very different view and representation of Edinburgh compared to the romantic paintings we had seen previously. We looked at the work of Hill and Adamson, who (I had not realised) had paid particular attention to Edinburghs architecture. In fact, Forbes informed us that Hill was actually a very political figure who was part of a massive attempt to reclaim art from the aristocracy.

Figure 1: Edinburghs Scott Monument Under Construction, c1844David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson.

Through this new photographic documentation of Edinburghs architecture, the city was being actively monumentalised. Edinburgh was transforming rapidly. Capitalism was now firmly entrenched as the dominant system of production, and thus changes within the local environment were inevitable: urban demolitions were common. In turn, the increasing rationalisation of modernity, as famously depicted by Max Weber, became entrenched in photography – the romanticisation of the past went hand in hand with its increasing commodification through the medium of photography. Forbes quoted Benjamin in saying that the truth of an object is only visible in its destruction. This discussion of destruction led us on nicely to Francis McKees paper.

Francis McKee offered us a discussion based on his current interest in the internet, modern ruins and their relationship to photography. McKee illustrated his talk with images of modern ruins from internet sites to demonstrate their increasingly popularity as an internet genre.

He spoke about the ruin as a modern invention that we humans have a great unspoken excitement and fascination with. His talk looked at various artists who have been inspired by ruins, from writers who remarked at the dark and wonderful nature of the Blitz, to filmmakers who were inspired by bombed-down cities to make movies (known as Rubble Films). He also analysed more recent examples of photographers who engaged with ruined sites such as Chernobyl, Beirut, Ground Zero and contemporary Detroit. McKee rightly questioned why people are so interested in these types of ruins. Where is photography now? And how is photography related to these sites?

Figure 2: Getty Caption: A milkman delivering milk in a London street devastated during a German bombing raid. Firemen are dampening down the ruins behind him. Photographer Fred Morley.

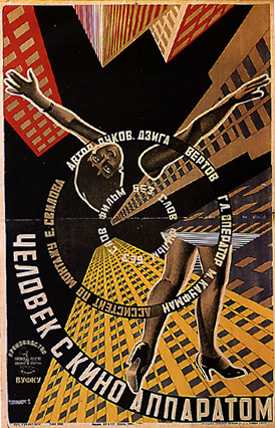

Figure 3: Original film poster for Rubble Film, c, 1929, Man with a Movie Camera

Figure 4: Michigan Central Train Station, Detroit. Image taken from the Internet site Flikr

McKee argued that the ruin might be becoming a fetishised symbol for photographers as a reaction to hyper media. Indeed as a photographer, I fully appreciate the temptation to document these ruins as they some how seem to encapsulate the past and present simultaneously.

The discussion ended on the somewhat depressing note that our experience of the city is becoming increasingly mediated, and that Art and photography still shape our imagination of the city. Some say that the city is dead yet McKee also suggested that maybe photography is dead. Today, we occupy a whole new social way of taking and receiving photographs. Controversially McKee suggested that maybe this new currency is much more important than Fine Art Photography. Although this was a somewhat pessimistic point to end on, it is a challenge for us photographers to grapple and engage with…

Caroline Douglas

Caroline Douglas is an artist based in Glasgow who predominantly works with photograpy. She was Artist in Residence at Stills Gallery in Edinburgh in 2008. She graduated in 2006.